“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” George Santayana

The lights began to go out all over Europe on June 28th 1914 with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. By July 28th the European continent was at war and, one hundred years ago today, the darkness arrived on the shores of this island as war was declared between The British Empire and Imperial Germany.

Why am I telling you this? Well, because my other affliction apart from woodworking is early twentieth century history, the events that led to World War One and its aftermath. In particular I am interested in early aviation: It was the engineers and the woodworkers of the time that made early flight possible. The fragile airframes of the early part of the war were almost entirely made from wooden frames that were held together with wire and covered in linen. Many industries on both sides of the conflict, including the furniture trade, turned their facilities and the skills of their craftsmen over to production of these new machines of war. Companies such as HH Martyn (below) who originally made the fixtures, fittings and furniture for luxury liners suddenly became aircraft manufacturers.

The learning curve was brutal and lessons were paid for in the lives of aircrew lost. The forces placed upon delicate flying surfaces were not well understood and lessons on the effects of both battle damage and weather on wood, glue, metal and fabric were painstakingly learned failure by failure.

Even as early as 1915 the technology had begun to mature with a reduction in the woodworking skills applied to these fast-developing machines of war and an increase in repeatable industrialised processes. Where possible many joints applied to early Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c scouts were therefore reinforced with metal brackets (shown below) – a technique used by Allied aircraft manufacturers through to the war’s end and beyond.

The designers emlpoyed by the Central Powers took a different route: Ever innovative, the German Roland company’s D.VI featured a highly streamlined fuselage constructed from overlapping plywood ‘planks’ in a manner similar to ‘clinker built’ boats. In contrast the Albatros Flugzeugwerke began building what were effectively early wooden monocoque structures (below).

With the recent surge in interest due to the conflict’s centenary, the activities of many woodworkers who are bringing some of these fragile and dangerous machines back to life is being recognised. They range from lone woodworkers working in a garage to huge commercial operations.

Nick Caudwell in Australia (above) has spent nine years recreating a late war Sopwith Snipe from nothing but the period Sopwith drawings. Koloman Mayrhofer and Eberhard Fritsch have spent thousands of hours handcrafting the structure of an Albatros D.III (below, which flew for the first time in 2012).

Surely the most impressive of these efforts however is the operation put together by Sir Peter Jackson the film director who, due to his obsession with the period and vast resources has recreated many of the aircraft of the time through his company ‘The Vintage Aviator’ (TVAL).

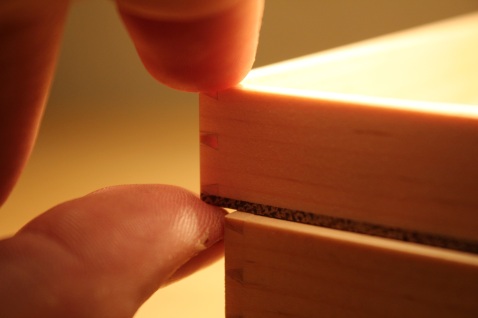

Mostly, the craftsmen who work at TVAL did not, like the lone builders before them, have anything other than the imperfect and often incomplete drawings of the machines of the time to go by. But, as a result of a huge effort, this endeavour is probably unique within the world aviation community due to the fact that it solely manufactures aircraft from the 1914-1918 period. TVAL work under strict Civil Aviation Authority mandates, codes and systems for their methods of construction and operation; Safety is paramount.

The TVAL staff has a great deal to be proud of; a state of the art manufacturing facility coupled with an ICAO Aircraft Manufacturing approval. These two remarkable achievements emphasize their commitment to engineering excellence and technical innovation. TVAL are using the most modern technology to reproduce the most accurate aircraft reproductions from a bygone era. I don’t often point at things outside of woodworking for furniture but the quality of the woodworking alone, as the photos show, is extremely high.

The war that began a century ago destroyed tens of millions of lives, ruined empires and bankrupted nations. Its brutal mechanisation and mass industrialisation also changed the course of art and damaged the craft tradition in many nations including that of woodworking. By 1918 aircraft 9and everything else were made to industrial processes in large scale factories rather than the workshops of 1914; The war halted any serious development of lyrical and labour intensive design styles such as Art Nouveau as artists and designers replaced the natural forms of Art Nouveau with those that represented mechanisation and speed as Art Deco became ascendant.

Today I wanted to do two things: first to point at some of the incredible work being done by some really committed woodworkers that help us to remember the past but most importantly to remember all those who were caught up in the maelstrom of that dreadful summer a century ago.

– Paul Mayon